TELEVISION'Mister Rogers' Ends Production, but Mr. Rogers Keeps BusyBy DOREEN CARVAJAL

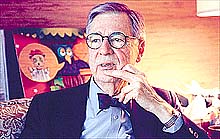

But the man presiding over Neighborhood Vérité in a cluttered wing of WQED, the public television station here, is far more comfortable than his old shoes. At 73, Fred Rogers is savoring his evolving roles as a television host emeritus, elder sage and chairman of his own nonprofit children's-issues think tank and production company, Family Communications Inc. Mr. Rogers has largely shed his signature uniform of a hand-knit sweater for a professor's garb of bow tie, navy jacket and spectacles. But he still leads with the same soft, patient voice that soothed generations of young viewers mourning dead goldfish or harboring fears of unruly vacuum cleaners. Some of those television fans harbor the mistaken notion that Mr. Rogers has taken refuge in retirement since his company announced in November that it would soon tape the last new episode in his 33-year-old series. But he will remain a television perennial; his last week of episodes, focusing on the arts, will be shown in late August and then will be recycled along with 300 other shows (out of 1,700 he made) in a seamless, never-ending loop. Meanwhile Mr. Rogers arrives for work daily in his cramped corner office, where he really, really likes things just the way they are. He is surrounded by 15 employees, some of whom have worked with him for decades, including Mr. McFeely, the Speedy Deliveryman, who in reality is David Newell, longtime director of public relations. Impromptu staff meetings take place in Mr. Rogers's office at the seats of power and frump: a vintage 60's couch of gold paisley, its pillows supported by a wooden plank, and a roomy leather chair. The furnishings rarely changed through three decades even as his show evolved from a black-and-white local production to a national powerhouse that reaches more than 3.5 million viewers weekly through more than 300 public television stations. In the new post-"Neighborhood" era, Mr. Rogers's evolving projects will mix his low-key style, which featured 30-year-old hand puppets and a cardboard castle, with the high gloss of new technology. There are discussions about creating bedtime stories on the Web delivered nightly by Mr. Rogers in streaming video. His Web site — www.misterrogers.org — is quickly expanding its offerings with tips for parents from toilet training to play activities. And Family Communications is studying radio-satellite technology that could also distribute the bedtime stories. The Henry Buhl Jr. Planetarium and Observatory in Pittsburgh is negotiating national distribution of its new planetarium show, a computer- animated 3-D version of "The Sky Above Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood," which features Mr. Rogers and his puppets. This year Running Press published "The Giving Box," a book by Mr. Rogers dispensing advice about charity for beginning preschool philanthropists. Next to come is a novelty book of magnetic "Neighborhood" postcards aimed at a college market that remains a base of devoted fans. In the midst of this activity, Mr. Rogers — who meticulously wrote all the songs and the scripts for his television series — says he is utterly relieved that the taping has ended. He could still make another "Neighborhood" in the studio downstairs, where familiar props like Henrietta Pussycat's tree are displayed. Yet Mr. Rogers betrays no yearning for a comeback: "I really respect opera singers who stop when they feel that they're doing their best work." Everywhere that the chairman of Family Communications wanders there are concrete reminders of his make-believe world. The Pittsburgh Children's Museum houses a permanent "Mister Rogers" exhibit where children can drive his familiar trolley. The University of Pittsburgh boasts an archive of "Neighborhood" shows, with the most requested episodes including one about the death of a goldfish and a special after the assassination of John F. Kennedy. When Mr. Rogers and his wife of 48 years, Joanne Rogers, take a walk, strangers spontaneously warble, "It's a beautiful day in this neighborhood." The choruses amuse them, but Mrs. Rogers, a concert pianist, said her husband was satisfied to put the show behind him. "He doesn't miss the show," she said. "I think he misses the Neighborood of Make-Believe because he enjoyed working with people around him. He really loves all of them, and he'll keep in touch. But he did not enjoy what he called `interiors,' the beginning and endings of the programs. He had gotten where he had really dreaded it so." The sweater-donning openings were his signature scenes, the subject of "Saturday Night Live" parodies and other spoofs. But Mr. Rogers privately came to loathe the need to wear television makeup and contact lenses for the segments. "I don't know why," he said. "It has something to do with I like to give myself as I am. In the early days you could do that." More than five years ago Mr. Rogers started privately considering ending the show after the death of his longtime music director and pianist, John Costa, whose jazz gave the show its distinctive musical personality. But he pressed on, partly because he felt responsible for the staff members who inhabited the real "Neighborhood," which had the simple warmth and loyal relationships of the make-believe version. Hedda Bluestone Sharpan, an employee of 33 years, recalled moments when her boss shared conversations about her ailing cat and then offered to join her when it was euthanized. They thought of themselves as sort of a church congregation with a "sense of being involved in something bigger," said William Barker, a friend of Mr. Rogers who was the voice of the puppet Dr. William Duck Platypus. Because of that atmosphere, Mr. Rogers, an ordained Presbyterian minister "carried on the program longer than he might have thought was a good idea simply because of the other people who were involved in it," Mrs. Rogers said. "Then he finally decided that it had to be done." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ITTSBURGH — Inside the reality

version of "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood," the office closet is stocked

with jackets instead of zippered cardigans. Nearby, a familiar pair of

blue sneakers is tacked like a rare butterfly in a plexiglass shrine.

ITTSBURGH — Inside the reality

version of "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood," the office closet is stocked

with jackets instead of zippered cardigans. Nearby, a familiar pair of

blue sneakers is tacked like a rare butterfly in a plexiglass shrine.